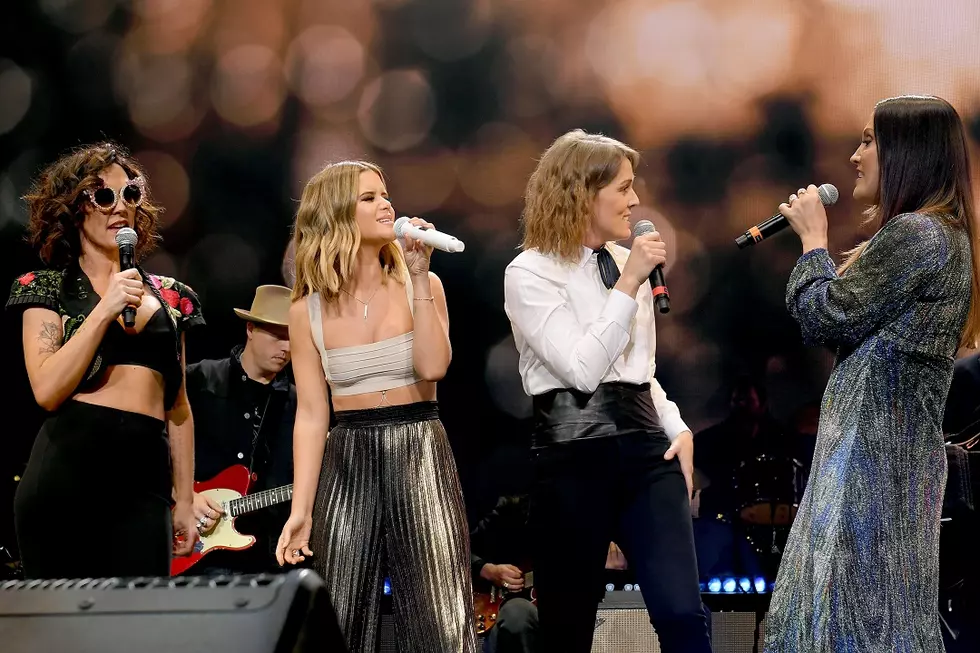

Op-Ed: Let ‘The Highwomen’ Be a Doorway to Country Music’s Lesser-Known, Under-heard Stories

When the Highwomen were putting together the songs for their self-titled debut project, bandmate Brandi Carlile tells Esquire, the group brought their message of community and solidarity to every aspect of the album -- even its brass tacks.

"[Engineer] Tom Elmhirst kept sending me these mixes, and I just couldn't put my finger on what was wrong with the vocals. I started getting really molecular about what was going on with my headphones, and I noticed that they were panned, in a sense," Carlile explains. "So there was Natalie [Hemby] here [at one level], Amanda [Shires] here, Maren [Morris] here and me here.

"I told him, 'It’s going to go against everything you believe in, but each of the voices needs to come at us all at one volume — mono — through the speakers. No panning, no left and right. No anybody louder than anybody else,'" she continues. "When he sent it back, he was like, 'I love it. It’s totally new.'"

In other words, the Highwomen have no real frontwoman, no vocal hierarchy. The track listing for their self-titled debut album, released on Friday (Sept. 6), names all four members -- and some guests, including Yola -- by turns as both lead and backing vocalists, and sometimes, all are listed as both, in the same song. That's by design: The group was conceived as a radical restructuring of what a country group looks like, not least of that being its emphasis on community between women and a fundamental lack of competition or opposition between female artists.

"Our goal is simply to elevate all women and completely abandon the concept of competing with one another," Carlile explained to The Boot and other outlets earlier in 2019. "So that we can let as many women through the door as possible and give our girls those country music heroes that we all had."

The Highwomen represent a new and particularly potent chapter in the long, tumultuous history of country music and its outsiders.

The female country icons that inspired Carlile and her bandmates are self-apparent in the Highwomen's music, much of which takes stylistic cues from the genre's artists from the 1970s and '80s. Matter-of-fact kiss-off tracks such as "Don't Call Me" include deadpan, spoken-word quips ripped right out of Loretta Lynn's playbook; "My Only Child"'s somber, eerie three-part harmony calls folk group the Roches to mind.

It's a well-documented phenomenon that women's place in country music has grown slimmer since the '90s; however, it's a mistake to assume, as a recent New York Times article about the band suggests, that country music today is a complete boys' club, and the Highwomen are here to singlehandedly correct that. It isn't as if this supergroup sprung forth, fully formed, from a morass of "bro country," pedal steel guitar in hand, ready to take back the place in country music that women used to occupy. Things -- as they're wont to be -- are not that simple.

Instead, the Highwomen represent a new and particularly potent chapter in the long, tumultuous history of country music and its outsiders. The past several years have been eventful ones for the problem of bias against women in country music, from 2015's "Tomatogate" to the solidarity that helps lift up rising female artists in a cutthroat industry. In 2019 alone, a swath of all-women tours (helmed by Morris, Carrie Underwood and Miranda Lambert, to name a few) have demonstrated that not only do female artists not need to compete with each other, but that an all-women bill can sell out amphitheaters.

The response to the Highwomen should be not to deify these four women and the album they've made, not to champion them as the sole fixers of a longstanding problem in country music, but to *pay attention*.

Even before Keith Hill's comments about women being the "tomatoes" in the metaphorical country music salad galvanized their place on country radio, all-female supergroups played an important role in the genre. The Pistol Annies, comprised of Lambert, Angaleena Presley and Ashley Monroe, debuted in 2011; decades earlier, Dolly Parton, Emmylou Harris and Linda Rondstadt released Trio in 1987. Like The Highwomen, that album features a flair for the traditional, with standards including "Farther Along" and "My Dear Companion" dotting its track list. After its release, Trio netted a Grammy for Best Country Performance By a Duo or Group With Vocal in 1988, as well as the title of Vocal Event of the Year at the 1988 CMA Awards and Album of the Year at the 1987 ACM Awards.

Of course, the Highwomen have never claimed to be the first of their kind. If anything, the opposite: Both music and message are rich with history, and rich with the female icons on whose shoulders they stand.

The temptation in listening to the Highwomen is to hail them as unprecedented. Many have billed their song "If She Ever Leaves Me" as the "first gay country song," for example, but both decades past and recent history in the genre prove otherwise. Given the Highwomen's message of inclusion, the best response to "If She Ever Leaves Me" is not to celebrate it as country's first same-sex love song, but instead to wonder whether or not it is -- and then to go looking for other examples. As a whole, the response to the Highwomen should be not to deify these four women and the album they've made, not to champion them as the sole fixers of a longstanding problem in country music, but to pay attention.

Pay attention to the untold stories -- which, it often happens, are not untold at all, but rather unlistened-to -- that the Highwomen bring to light. Pay attention to Our Native Daughters, the criminally under-recognized group that Rhiannon Giddens, Amythyst Kiah, Leylan McCalla and Allison Russell formed in early 2018 to re-imagine traditional, ancient folk songs. As much as they are the architects of a new era of country music, the Highwomen are also a doorway to country music's important, but lesser-known, recent past and present day.

More of Country Music's Modern Female Trailblazers

More From 95.3 The Bear

![Maren Morris Goes Solo for ‘Crowded Table’ Live on Tour [WATCH]](http://townsquare.media/site/623/files/2019/09/maren-morris.jpg?w=980&q=75)